On October 7th 2022, Michael Nylan, professor of history at University California Berkeley gave an online lecture under the title “Xue 学: ‘Learning and Emulation’”. This was the third lecture in the “Collaborative Learning” (Si Hai Wei Xue 四海为学) series hosted by the Philosophy Department at ECNU. The lecture was chaired by Dr. Sarah Flavel (Bath Spa University) and comments were provided by Prof. Richard King (Bern University) and Prof. Trenton Wilson (Princeton University).

What does it mean to learn? The extended title of Professor Michael Nylan’s October 7th online lecture was “Xue 學: Learning and Emulation in the Early Empires in China.” In it she discussed what learning meant for thinkers of early China and what these insights might mean for the modern world. Unlike modern understandings of education as book learning, ancient thinkers understood learning as encompassing both practice and praxis, and always with an eye towards solving practical concerns.

The lecture was divided into three sections. The first section discussed the nature of manuscript culture and the nomenclature for classical learning. The second focused on the models, sources, and objects for learning and emulation, and the final section explained the notion of the wise person in the early tradition.

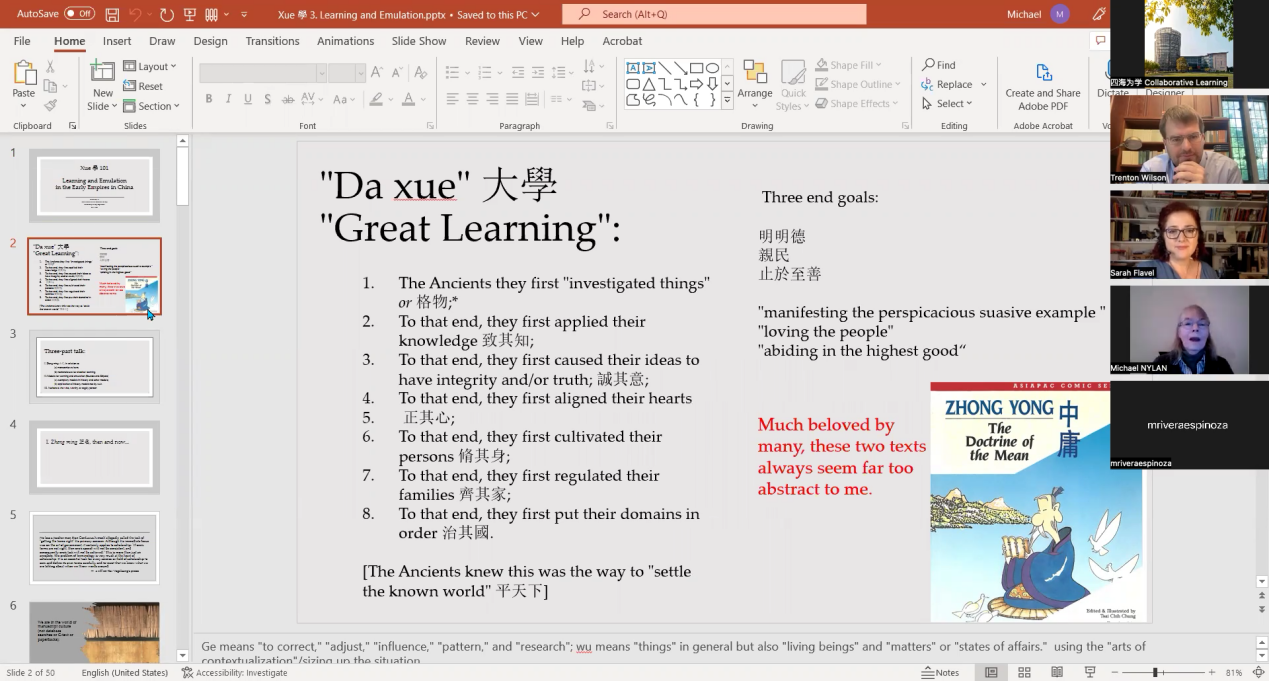

In the first section of the lecture, Professor Nylan emphasized that the world of early manuscript culture differed greatly from later periods. This period was not defined by a single China with an official canon but was a world of many small textual communities. We often forget the nature of the world in which these manuscript cultures developed. The transmission of manuscripts was connected to practical concerns and, in particular, their capacity to offer solutions for the governing elite. The solutions and views of these texts cannot be understood as being divided into the “moral” and “pragmatic” solutions. Any political solution needed to address the interests, opinions, and feelings of the people involved and affected by the political decision.

These elements are critical to all aspects of manuscript culture. Oral transmission, teaching, and the ritual encounters that serve to transmit such teachings were central to these cultures. The education of these textual experts was not necessarily focused on a particular classic but rather on one of many readings of a classic that were in co-circulation. The authority of the text came not from the text itself but the authoritative figures connected with it. In addition, these textual experts were not separated from the world of action, and many of these experts served in political positions. Their education earned them several kinds of authority, from status and office-holding to wealth and access to special expertise.

The second section discussed the sources of emulation. Professor Nylan pointed out that insights were often found in divinations, dreams, history, and formal or informal discussions. Of these sources, Professor Nylan focused on the importance of history, not as an abstract theory or as an object with an internal logic of necessary progression, but as something that could be studied to gain insights into how to operate within the governing elite. Historical examples could be studied and emulated. By reading histories, learners could rehearse historical situations as a way of facing political and social crises.

History as concerned with ancient exemplars and heroes is a perspective that differs from many modern approaches. There is a sophistication and subtlety in ancient approaches to ancient exemplars. What might make someone exemplary or worth emulating may differ in regard to the needs of a specific situation, and there were no universal and invariant rules as to how one might respond to a crisis. The focus when looking at history was on finding guidelines of how to act in concrete situations of the present or future.

Such subtlety and complexity is found in the presentation of controversial figures throughout many different texts. To illustrate this, Nylan drew upon Christian Schwermann’s research on the nature of anecdotes. Anecdotes often appear in multiple sources, but they are not always used to express the same idea. The idea of concept clusters is used to explain this. In ancient texts, controversial figures could appear with other historical exemplars, and the clustering of these different figures added new meanings and significance to those whose status was debated.

In contradiction to this, modern scholarship often approaches exemplary figures in a much more simplified way: we see figures as either good or bad, and as individuals cut off from the networks to which they belonged and the historical environment in which they lived. Further, in contrast to ancient thinkers, our own approaches often separate moral from pragmatic concerns.

The third and final section discussed what characteristics made a person wise in early Chinese culture. Those worthy of emulation were not lofty or transcendent figures detached from the world, but those who were worried about and worked for the benefit of others. Professor Nylan noted several metaphors that stress the focus on practice and the practical: the learned or worthy person was an archer who could reliably hit a target every time, or poet who was both well-read as well as active in the creation of their own poetry. As emphasized in the presentation: “everything boils down to praxis, not book learning.”

Markedly different from many later and more modern conceptions of heroism, ancient heroes and models were also those of a marked epistemological modesty. They had flaws, and many saw the dangers of lofty heroism that was pursued at all costs. This is clear from the famous story of Weisheng 尾生, told in the Daozhi 盗跖 chapter of the Zhuangzi 庄子, in which Weisheng insists on honoring his appointment to meet a lady beneath a bridge, even as the river rises and eventually drowns him. Epistemic modesty was also expressed in the willingness of worthy and learned figures to ask questions and listen to others, as noted in the Analects 3.15 where Confucius is ridiculed for asking about every matter whenever entering an ancestral temple. The ability to listen to one’s subordinates was particularly important for those holding political power. It was a way of restraining negative inclinations or overconfidence in their own abilities.

The presentation was followed by comments from Professor Richard King of Bern University and Professor Trenton Wilson of Princeton University, and several questions from the audience. A follow-up discussion is scheduled for the same time in the following week.

Report by Jordan Davis

Betway必威主页

Betway必威主页 校内链接

校内链接 校外链接

校外链接 校内邮箱

校内邮箱